🧠 2025 LLM Limitations: Research Review on the Real Boundaries of AI Reasoning

Table of Contents

Introduction: The Dazzling—and Deceptive—Facade #

The pace of progress in AI is nothing short of breathtaking. Capabilities that seemed decades away—like robust translation or high-quality text summarization—are now readily available, powered by Large Language Models. I still remember the effort required to train a domain-specific NER model; today, the same task would take an order of magnitude less time and data.

And yet, while these models can perform with the fluency of an expert, there’s a persistent feeling that something is missing. They provide genuinely helpful assistance in many tasks, but to me, it is still a facade of intelligence,

However, beneath this impressive surface, a different story is unfolding. The widespread hype proclaiming the imminent arrival of AGI often overlooks the concerns of respected figures like Yann LeCun and Gary Marcus, along with a growing body of methodical research that reveals deep and fundamental limitations in how these models “think”.

This post is a journey behind that facade. Guided by a spirit of critical optimism, we will analyze the key findings from recent studies that test the limits of LLM reasoning. My goal is not to be cynical, but to be realistic—to understand what these systems truly are and what they are not. I’m driven by a principle: you must first understand a system’s boundaries before you can find a way to break through them.

The Measurement Problem: What is “Reasoning” Anyway? #

Before we can analyze the boundaries of the reasoning capabilities of the LLMs, we have to address a foundational challenge: what do we even mean by “reasoning” or “intelligence”? These concepts are notoriously difficult to define, and without a widely accepted scientific consensus, any debate on whether LLMs are truly “intelligent” quickly becomes a unproductive philosophical dispute. The conversation is even more complicated in public forums where everyone brings their own definition to the table.

Rather than getting lost in semantics, this post will take a more empirical approach. Instead of trying to define what reasoning is, we will test what today’s models can’t do. By examining the specific points where their performance breaks down. We can gain a much clearer, evidence-based understanding of their true capabilities and limitations.

Cracks in the Facade: Mapping the Boundaries of Reasoning #

It’s important to state that LLMs are powerful tools that are changing how we work. The goal here is not to dismiss their capabilities, but to understand them with scientific rigor. The research I’ve followed helps define their current limitations—or, perhaps more constructively, their operational boundaries.

Synthesizing the findings from several key studies reveals recurring themes where the facade of intelligence begins to fade.

1. Brittle Logic and Faulty Generalization #

A common thread in the research is that LLMs rely on surface-level patterns and statistical correlations rather than abstract logical rules. They often lack a deep, grounded understanding of the concepts they discuss. Their “reasoning” is therefore brittle—it works well when a problem’s structure mirrors the training data but can shatter when the format is changed, even if the underlying logic remains identical.

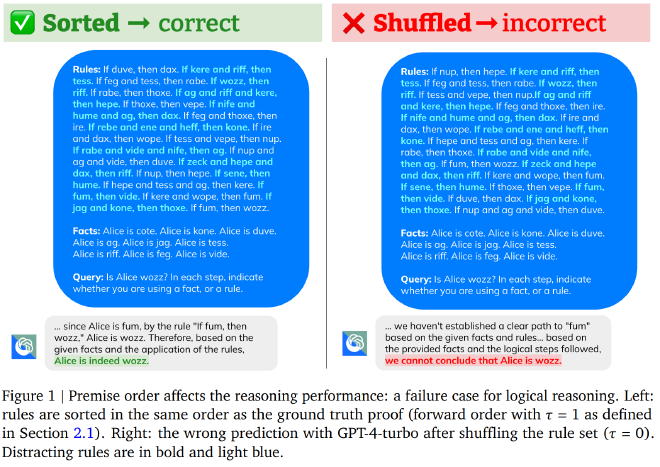

A stark example comes from the DeepMind “Premise Order Matters”1 study. It found that simply reordering the premises in a logical problem could cause a model’s performance to plummet by over 30%, while similar test performed on humans present only slight degradation, where premises order was disturbed drastically (randomly).

This extends to distractibility, where introducing irrelevant facts can similarly derail the model’s reasoning, a phenomenon explored in studies on the “Distraction Effect”2 and cognitive biases3. A system that truly grasped the logical connections would be indifferent to presentation order and easily ignore such distractions. Similarly, the GSM-Symbolic benchmark showed that changing only the numerical values in a grade-school math problem was enough to significantly degrade accuracy. The models had memorized the pattern of the problem, not the mathematical principles.

This failure to generalize is also captured by the “Reversal Curse.”4 This is the finding that a model fine-tuned on “A is B” often fails to generalize to “B is A” when queried later. It highlights a failure to learn a simple, symmetric property of facts from training data, instead learning a one-way statistical association. These examples point to a fundamental limitation: the models are learning to be sophisticated mimics, not flexible, principled reasoners.

2. The Overthinking and Absence of Critical Thinking #

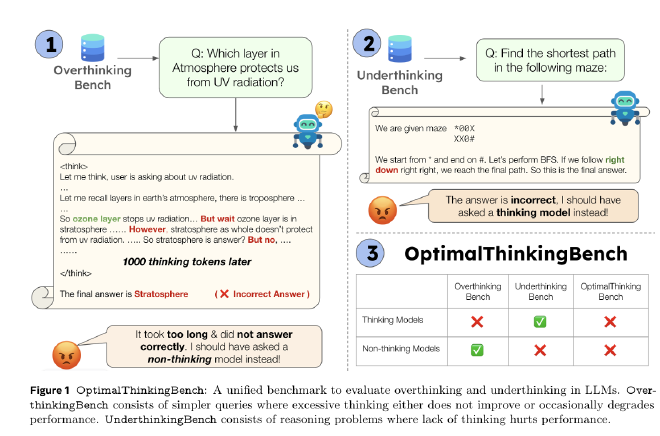

Beyond brittle logic, a deeper limitation emerges: a lack of critical thinking. This manifests in two opposite but related failures: models often “overthink” simple or unsolvable problems, yet “underthink” when faced with true complexity or the need for deep causal analysis.

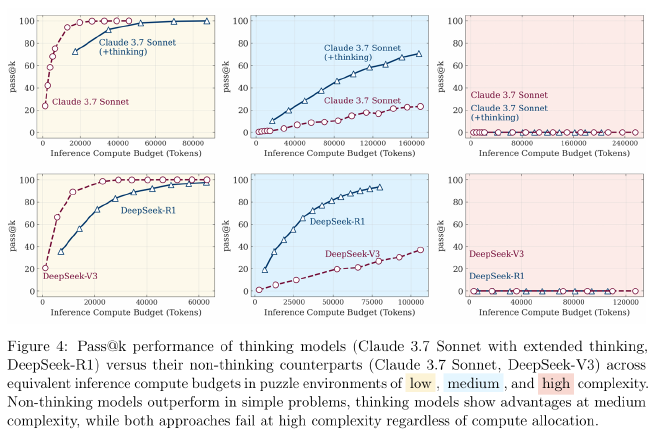

The Apple paper, “The Illusion of Thinking,”5 provides a clear example of both extremes. Researchers tested models on classic puzzles like the Tower of Hanoi, Checker Jumping, River Crossing etc, where complexity can be precisely scaled by the number of steps. For simple problems, reasoning-heavy models often overthought their way, performing no better than non-thinking counterpart models while being far more computationally expensive. But when faced with a truly complex puzzle, the models didn’t just fail; they hit a “complexity cliff” and effectively gave up, revealing a fundamental inability to manage and persist through complex, structured tasks.

This tendency to overthink is mirrored in the “Missing Premise exacerbates Overthinking”6 study. When given an ill-posed question with information missing, reasoning models don’t recognize the problem’s unsolvability. Instead, they generate long, redundant, and ultimately useless chains of thought. A truly critical system would identify the missing premise and state that an answer is not possible.

This is further explored in the research that introduces OptimalThinkingBench7, a benchmark that jointly evaluates overthinking on simple queries and underthinking on complex ones. The study reveals that even the most advanced models struggle to find an optimal balance, with “thinking” models wasting compute on simple tasks and “non-thinking” models failing on difficult ones. This highlights a fundamental trade-off in current architectures and the need for models that can dynamically adapt their reasoning depth to the problem at hand.

Finally, this lack of critical thinking extends to understanding causality. As the “Cause and Effect”8 paper explores, models can identify statistical correlations but struggle to grasp true causal relationships. This is a form of abductive reasoning—inferring the most likely cause—where models consistently fall short. They can tell you what is associated with something, but not necessarily why.

3. The Measurement Mirage: Are We Seeing True Emergence? #

Finally, we must question how we measure progress itself. An idea that captured our imagination in recent years has been that of “emergent abilities”. Capabilities that seem to appear suddenly and unpredictably in LLMs once they reach a certain scale. We wanted to believe that the spark of intelligence appears while scaling the model size, it feels like we found the holy grail to unlock the AGI.

However, a critical paper from Stanford University, “Are Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models a Mirage?”,9 offers a compelling counter-argument. The researchers found that these “emergent” leaps are often an illusion created by the metrics we choose. When a task is measured with a nonlinear, all-or-nothing metric (like “exact match accuracy”), performance can look like a sharp, unpredictable jump from failure to success. But when the same task is measured with a more continuous metric (like token edit distance), the improvement is revealed to be smooth, gradual, and predictable.

This doesn’t mean large models aren’t capable, but it suggests we are not witnessing spontaneous leaps of intelligence. Instead, we are observing the predictable consequences of our own evaluation methods. It’s a powerful reminder that in the quest for AGI, what we measure and how we measure it profoundly shapes the reality we see.

Conclusion: Beyond the Facade #

The evidence is clear: the brittle logic, the absence of critical thinking, and the measurement mirages all point to the same conclusion. Today’s Large Language Models, while remarkable, are not fledgling AGIs but sophisticated simulators of intelligence. They are masters of statistical pattern matching, producing a fluent and useful facade of reasoning without genuine understanding. This is the core of the “stochastic parrot” metaphor—they know what an answer should look like, but not what it truly means.

This is a realistic, not pessimistic, diagnosis. Acknowledging the boundaries of the current paradigm is the first step toward breaking through them. The path forward is not simply about scaling what we already have, but about fundamentally rethinking what is missing. From my own observation and intuition, building the next generation of AI will require us to focus on several key areas:

- A Persistent State of Mind: We need systems with robust, short-term memory that allows them to act on recent events and maintain context, much like a mental “scratchpad.”

- Continuous Learning: Connected to this, models must be able to learn from feedback at inference time. A truly intelligent system updates its knowledge based on new input, rather than being a static, pre-trained artifact.

- A “Living” Cognitive Architecture: This leads to a model whose mind is in a constant, “beating” state—continuously processing and analyzing inputs, not just operating in simple, reactive prompt-response cycles.

- An Internal Critic: A crucial missing piece is a meta-cognitive module—an internal critic or router that can categorize the problem it’s facing (simple, hard, or ill-posed) and recognize when it should be confident versus when it should abstain.

- Controlled, Creative Hallucination: While we fight against factual hallucinations, we must also recognize the need for a kind of “conceptual hallucination”—the ability to find novel analogies and forge new relationships between ideas, which could lead to new insights and discoveries.

The goal isn’t to diminish what LLMs have achieved, but to be honest about the journey ahead. By focusing our efforts on these deeper challenges, we can move beyond the facade and begin building the next generation of truly intelligent machines.

Further Reading #

- LLMs are not like you and me—and never will be - Gary Marcus, Aug 2025

- A knockout blow for LLMs? - Gary Marcus, Jun 2025

- Yann LeCun on a vision to make AI systems learn and reason like animals and humans - Yann LeCun, Feb 2022

References #

Premise Order Matters in Reasoning with Large Language Models, https://arxiv.org/pdf/2402.08939 (2024), DeepMind ↩︎

Large language models can bbe easily distracted by irreleveang contex, https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.00093 (2023), F. Shi, X. Chen, K. Misra, N. Scales, D. Dohan, E. H. Chi, N Scharli, D. Zhou ↩︎

Capturing Failures of Large Language Models via Human Cognitive Biases, https://arxiv.org/abs/2202.12299 (2022), E. Jones, J. Steinhardt ↩︎

The Reversal Curse: LLMs trained on “A is B” fail to learn “B is A”, https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.12288 (2023), L.Berglund, M.Tong, M. Kaufmann, M. Balesini, A. C. Stickland, T. Korbak, O. Evans ↩︎

The Illusion of Thinking: Understanding the Strengths and Limitations of Reasoning Models via the Lens of Problem Complexity, https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.06941 (2025), Apple ↩︎

Missing Premise exacerbates Overthinking: Are Reasoning Models losing Critical Thinking Skill?, https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.06514 (2025), Ch. Fan, M. Li, L. Sun, T. Zhou ↩︎

OptimalThinkingBench: Evaluating Over and Underthinking in LLMs, https://www.arxiv.org/abs/2508.13141 (2025), Meta ↩︎

Cause and Effect: Can Large Language Models Truly Understand Causality?, https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.18139 (2024), S. Ashwani, K. Hegde, N. R. Mannuru, M. Jindal, D. S. Sengar, K. Ch. R. Kathala, D. Banga, V. Jain, A. Chadha ↩︎

Are Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models a Mirage?, https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.15004 (2023), Stanford University, NeurIPS 2023 ↩︎